Contact With the Human Race

The Significance of the

Aliens in Amused to Death

by Mike McInnis

Amused to Death is a profoundly dense album, lyrically speaking, rich

with allusions, accusations, and a few personal attacks. It isn't the sort

of music you really grasp after only a few listens. It demands scrutiny and

attention to detail. And while Roger Waters, like John Lennon, Pete Townshend,

and other popular songwriters, has publicly accused fans and critics of reading

too much into his lyrics, I simply cannot help myself when it comes to masterworks

such as Amused to Death (and The Wall, and The Dark Side

of the Moon, and so on).

One of the most perplexing recurring images in Amused to Death is the aliens found in "What God Wants" parts 1 and 3, and in the title track. No matter how lyrical dissections I read, the presence of these aliens is never explained in a fully satisfying way.

The aliens first appear early on in the album, in "What God Wants, part 1". After the lists of things God wants, an alien prophet says, "Don't look so surprised/It's only dogma". Later, the alien comic tells the monkey that he's "only joking", but the implication is that he is really very serious (we are told that he is lying). The TV teaches the monkey lessons about what God wants, and the monkey learns that just about anything can be justified in the name of God.

| Issues of Stanley |

|

No look at the space-related imagery in Amused to Death

would be complete without at least a brief mention of the connection between

"Perfect Sense, part 1" and Stanley Kubrick's classic science fiction film

2001: A Space Odyssey.

The introduction of the song, as found on the studio album,

features a derisive backward message aimed at someone named "Stanley". This

has long been accepted as a jab at Kubrick, who denied Waters permission to

used a sample of dialogue from 2001 on the album. (On tour in 1999

and 2000, Waters used the sample as he originally intended--as a jab at David

Gilmour. This can be heard on In the Flesh.)

The connection to the film goes much deeper than this, however.

In a scene strongly reminiscent of the opening sequence of 2001, Waters describes

a monkey sitting upon a pile of stones with a broken bone in his hand. This

is the proto-human ape that killed another ape with a bone in 2001, contemplating

the murder weapon. The lyric also describes the sound of a Viennese quartet,

a direct reference to the use of Strauss' "Blue Danube" in the film's prolonged

space sequence that immediately follows the prehistoric ape sequence.

The song goes on to describe the moral and intellectual development

of the ape as he becomes human. Waters makes reference to the Garden of Eden (where,

in the Judeo-Christian tradition, the first humans lived), the development

of civilization, and the institution of war.

|

But why did Waters feel the need to make this prophet an alien? The word 'alien' could mean a person who is a foreigner (e.g "illegal alien"), but in the title song it is clear that these aliens are of the 'little green men' variety. Perhaps Waters was planting aliens in the lyrics early on in order to set the stage for his little science fiction twist at the end of the album.

The prophet and comic are most likely two faces of the same entity. Television has the power to be many things, and to convey the same message in different ways. Maybe the prophet/comic is the television (as is, I suspect, the priest in the first line of the song), and Waters is trying to say that television has become the central motivating force in this society of mindless monkeys.

By the time we get to parts 2 and 3 of "What God Wants", the album has begun to focus on war, greed, money, and how all three are intermingled in today's politics and media. God is portrayed as being just another money-grubbing person, or perhaps as a pawn of the powerful Market Forces that rob and plunder and justify it in the name of Freedom and God. "Don't be afraid it's only business," the alien prophet tells us. Apparently God's presumed interest in money is forgivable because it's business.

From here the album goes on to portray humankind as an uncaring, bloodthirsty race that watches itself commit suicide on the television, as our ability to feel and care about one another is gradually taken from us. "Amused to Death" brings this into focus with lyrics such as "And out in the valley warm and clean/ The little ones sit by their TV screens/ No thoughts to think/ No tears to cry/ All sucked dry/ Down to the very last breath". We are numbed to human pain and suffering, and we watch our own moral destruction on television because that is what we are accustomed to doing.

The collective voice of the human race describes our fate thus: "We watched the tragedy unfold/ We did as we were told/ We bought and sold/It was the greatest show on earth/ But then it was over".

Then, without warning, is the sci-fi twist that shows that even after all these years Waters still has a thing for space themes: "And somewhere out there in the stars/ A keen eyed-eyed look-out/ Spied a flickering light/ Our last hurrah" Somewhere, an alien species has been observing the human race, and in true sci-fi style, this no-doubt advanced species has been studying us without actually interfering.

The human race has run its course, whether by nuclear war or by sheer apathy, and the alien anthropologists who have been studying us descend to see if there is anything else to learn from us. "And when they found our shadows/ Grouped around the TV sets/They ran down every lead/ They repeated every test/ They checked out all the data on their lists/ And then the alien anthropologists/ Admitted they were still perplexed". The aliens are trying to decipher how or why we allowed our species to end so unceremoniously.

"But on eliminating every other reason/ For our sad demise/ They logged the only explanation left/ This species has amused itself to death" The alien logic: 'The humans were all watching television, so this must be the cause of death'. In truth, it is still unclear to me (even after all these years) if the human race is supposed to have nuked itself out of existence (hence the flicker of light that is described as our 'last hurrah'), or if we really did just become so fixated on watching life on TV that we forgot to get out there and live it.

Either way, the aliens have no previous experience with this kind of thing, and they do not understand what would cause us to allow this to come to pass without so much as lifting a finger to stop it. We have become content to watch our own demise rather than working on solutions to prevent it.

Mike McInnis is a staff writer for Spare Bricks. His 1997 analysis of Amused to Death is available online at The Bright Side of the Moon.

Floydian Places: Planet Arrakis

Waiting for the Worms

The best Dune (with music by Pink Floyd) you'll never see

by Rick Karhu

Four examples of some of the otherworldly and surreal design work H.R. Giger produced for Jodorowsky's ill-fated attempt at filming Dune. |

Most Pink Floyd fans will write it off as one of those persistent and annoying Internet legends: that Pink Floyd had agreed, at one time, to provide music for the film adaptation of Frank Herbert's 1965 epic science fiction masterpiece, Dune.

Like most legends, there are elements of fact and fiction at work here. Yes, it is true that Pink Floyd were to provide music for the film adaptation of Dune, however (and this is contrary to how the fictional part usually insinuates itself) it was not for David Lynch's 1984 film starring Kyle MacLachlan. And like many legends, the most interesting part of the truth is left out. Pink Floyd, in agreeing to provide music for the film, agreed to produce a double-album's worth of music. That's a double-album that will never be heard, sadly enough, as the film never got further than pre-production.

To understand how Pink Floyd were almost involved in creating music to accompany a film of Herbert's classic novel, we have to familiarize ourselves with cult director Alejandro Jodorowsky. Born in Iquique, Chile in 1929, Jodorowsky rose to notoriety in the '60s in Europe, dabbling in a surprisingly wide array of artistic endeavors, including theater, music, performance art, writing, and, strangely enough, both mime and comic strips. The breadth of his artistic endeavors hints at a complex and interesting filmmaker in the making, something that his work in the following decades would bear out. Many of his works deal with religious themes in surreal and unique ways.

Jodorowsky was the director and star of the surreal 1970 western El Topo. Although it is frequently hailed as a brilliant and original allegory about religion, Jodorowsky's best-known film would establish itself ultimately as nothing more than a highly praised cult film. (One of those who highly praised the film, incidentally, was none other than John Lennon himself, who proclaimed the film a masterpiece.)

Whether another project Jodorowsky attempted to launch shortly thereafter would have topped that will forever be a matter of hypothetical discussions. More than a decade before David Lynch would succeed in bringing Herbert's book to film, Jodorowsky envisioned a gradiose sci-fi world of sand and spice, worms and warring tribes. (Given its messianic overtones and quasi-biblical touches, Dune seemed almost tailored to Jodorowsky's obsessions.)

Unfortunately, the project was doomed from the start by the very enthusiasm that helped launch it in the first place.

To look at the enormous roster of famous artists Jodorowsky signed on to the project early on makes one wonder whether the director was a genius or a madman--or both. The list is startling. Salvador Dali, Orson Welles, David Carradine, Gloria Swanson, H.R. (Hans Rudy) Giger, Jean "Moebius" Giraud, Christopher Foss, Gong, Mike Oldfield, Tangerine Dream and many others. That "many others" includes Pink Floyd.

|

Jodorowksy's

films

|

|

Les

Tetes interverties (year unknown) |

The list of artists gathered for the film reads like a "too good to be true" proposition that came with a multitude of inherent problems. How any single human being could have corralled so many strong-minded artists in the first place is one such problem. How any producer could foot the bill for such a gathering is another. (It is said that Dali commanded a sizeable chunk of the film's budget for his services alone.) Jodorowsky, true to form, had a unique concept of the film's music, that each planet should have its own style of music. To achieve this goal, Jodorowsky enlisted the help of several rock musicians. In the midst of his negotiations with record companies, the director had a great idea. Why not enlist Pink Floyd?

At the time, Pink Floyd were recording Dark Side of the Moon at Abbey Road studios. What seems in retrospect highly unlikely, could have--and would have--happened. Pink Floyd was not yet the phenomenon that Dark Side would make of them. Jodorowsky arranged to meet the band and pitch his proposal to them in person.

The filmmaker was pleased to discover that the members of the band were fans of El Topo and, probably as a result, agreed to meet with him. The director described his fateful, and somewhat humorous, meeting with the band.

Upon arriving, I didn't see a group of musicians in the middle of making their masterpiece, but four young guys eating fried steaks. Jean-Paul [Gibon] and I, standing in front of them, had to wait for their voraciousness to be satisfied. In the name of Dune I was taken by an anger and I left slamming the door. I wanted some artists who knew how to respect a work of such importance for human consciousness. I think that they didn't expect that. Surprised, David Gilmour ran behind us giving excuses and made us attend the final mixing of their record. What ecstasy... After, we attended their last public concert where thousands of fanatics cheered.... They decided to participate in the film by producing a double album which was going to be called Dune. They came to Paris to discuss the financial part and after an intense discussion, we came to an agreement. Pink Floyd would do almost all the music of the film.

Even given the promising start, the film would never see the light of day. Not only was the sheer enormity of talent involved in the project a problem, but so was Jodorowsky's apparently schizophrenic approach to making the film (various sources indicate that the script for the film was ludicrious in its length and scope and that it the director changed it frequently on a whim.)

Author Herbert said that Jodorowsky "spent a couple of million dollars in pre-production of his version. He even hired Salvador Dali as his production designer. Nothing ever happened. I'm not quite sure why it fizzled. Without exaggeration, his script would have made an eleven-or-twelve-hour movie. It was the size of a phonebook. It was pretty anti-Catholic, too."

On top of that, the director was reportedly quite happy to exclude Herbert from the production entirely. Jodorowsky told the French publication Metal Hurlant Magazine: "I did not want to respect the novel, I wanted to recreate it. For me Dune did not belong to Herbert as Don Quijote did not belong to Cervantes, nor Edipo with Esquilo."

He was also quoted elsewhere: "I feel fervent admiration towards Herbert and, at the same time, conflict."

The collapse of the costly production was no surprise. Financial support for the bloated project dried up in 1976 and the film rights passed on to Dino de Laurentis who had originally intended it for director Ridley Scott. Although he was an obvious pick at the time, having just directed Alien, Scott passed on the project which opened the door for David Lynch.

By this point, the entire project had been reinvented and virtually all traces of Jodorowsky's original vision had been removed. (Although curiously the Lynch version employs a rock band, Toto, as well as Brian Eno for the film's soundtrack. This could be largely coincidental, however, since most of Lynch's films employ an eclectic mix of musical styles, including rock and roll.) What would it have sounded like, a Pink Floyd album of music for a film of Frank Herbert's Dune? One can only imagine.

Unfortunately, the financial collapse of Jodorowsky's film

marked the end of the road for his vision of the film as well as Pink Floyd's

involvement.

SOURCES:

Hotweird.com

http://www.hotweird.com/jodorowsky/disinfo.html

"Internet Movie Database"

http://www.imdb.com

"Dune: Jodorowsky's Magnificent Failure"

http://www.spiderstratagem.co.uk/failure.htm

"Museum Arrakeen"

http://www.fremen.org/museum/docs/movie.html

"History of the Film"

http://www.duneprime.f2s.com/history.html

"The Dune You'll Never See"

http://www.space.com/sciencefiction/dune_jodorowsky_991019.html

Rick Karhu is a staff writer for Spare Bricks. Special thanks to everyone at alt.fan.dune.

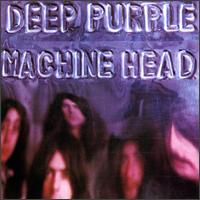

A Floyd Fan's Intro to Deep Purple's Machine Head

by Jacki Dimitroff

As

the psychedelic sixties turned into a seventies with attitude, I was barely

there to notice the change. However, being the younger sibling of two music-loving

sisters, I was exposed to all the latest rock elements. One particular album

that caught my attention at the time, and has remained as one of my all-time

favorites, is Deep Purple's Machine Head. Full of the attitude necessary

to help me in the transition from American elementary school to junior high,

Machine Head was instrumental in changing me from cello-wielding geek

to rock know-it-all. While the album was significant to me for my own reasons,

it took me quite a while to realize that Machine Head was important

to rock music itself.

As

the psychedelic sixties turned into a seventies with attitude, I was barely

there to notice the change. However, being the younger sibling of two music-loving

sisters, I was exposed to all the latest rock elements. One particular album

that caught my attention at the time, and has remained as one of my all-time

favorites, is Deep Purple's Machine Head. Full of the attitude necessary

to help me in the transition from American elementary school to junior high,

Machine Head was instrumental in changing me from cello-wielding geek

to rock know-it-all. While the album was significant to me for my own reasons,

it took me quite a while to realize that Machine Head was important

to rock music itself.

In the early seventies, heavy metal emerged as a new genre of rock. Pioneered by such bands as Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, and Deep Purple, heavy metal's attitude separated it from psychedelic rock, progressive rock, and space rock. Heavy metal developed out of hard rock, sharing the roots of blues, R&B, jazz and classical music, along with the very energetic drum/bass beat. Machine Head is one of the finest examples of how the fledgling genre distinguished itself from its predecessors.

Similar to early Pink Floyd, Machine Head has an amazing balance between the guitar and keyboards, both of which dominate the music's landscape. Listen to "Highway Star" and you're in for a magical treat of dueling instruments. To this day I am still wondering if the string effect found late in the track is actually a viola, two violas, or Jon Lord's keyboards (listen for the almost-undetectable changes in the stroke of the bow; they're very rapid, but not impossible for an accomplished musician). Add to that Ritchie Blackmore's harmonized double-tracked guitar solo and you have the perfect tune for riding down the highway in a convertible as the sun goes down on a summer evening.

Then there's the album's masterpiece, "Lazy," in which Jon Lord and Ritchie Blackmore show amazing insight for the musical excellence of the song. The opening falls just short of instrumental one-upmanship and blends into the perfect marriage of two artists' interpretations. It's a precise choreography of keyboards and guitar, and Ian Paice's drums add the perfect complement. This is the jam to end all live performances. It has the feel that it could go on in rambling improvisation forever, and yet has the tone of finality that the end of a rock concert needs. Like a good book, you never want it to end.

While Machine Head has equal moments of singular brilliance in this work between the guitar and keyboards (Lord's opening to "Lazy" vs. Blackmore's guitar phrasing during "Maybe I'm a Leo"), I find it impossible to discern one musician from the other as a dominating force on this album. This should entice Rick Wright fans and David Gilmour fans alike, who enjoy the early symbiosis of the two performers. However, Machine Head shares the power of both instruments throughout the album, so that the guitar and keyboards complement each other, and one never submits to the other.

Another important element of Machine Head is the drum/bass tandem of Ian Paice and Roger Glover. Like a great piece of architecture, this element is always present, but never superfluous. It creates the perfect structure for the creativity of Lord and Blackmore. But there are even moments in songs such as "Pictures of Home" and "Space Truckin'" where the drum/bass tandem takes center stage and fulfills its promise as a larger contribution to the overall tapestry. I have to ask myself if "Smoke on the Water" would be as powerful if it still held the infamous opening guitar riff, but lacked the underlying rhythmic structure.

While you shouldn't expect any epiphanies from the lyrics, you should understand that this album encompasses the blueprint for the subjects of heavy metal: bad women, fast cars, and parties that never ended. During the early seventies, "Smoke on the Water" set the standard for the genre, and literally draws on a true experience of multiple bands continuing the "party" despite dour circumstances. The song "Never Before" continues in the same manner, telling a woeful tale of misery from a bad woman, but adding an upbeat tempo suggesting the "rock on" mentality.

Meanwhile, the lyrics of "Highway Star" have a roughrider edge to them, eliciting images of lonely back roads whizzing by with the wind in your hair. Ian Gillian delivers the lyrics quite admirably, but I find his singing lacking the punch of a standout vocalist. However, while I never considered the vocals on this album to be spectacular, I understand that singers for many of the bands that followed Deep Purple consider Ian Gillian to be one of their biggest influences.

While listening to "Pictures of Home," I am struck by the ease in which this song encompasses the elements of psychedelic and yet still heralds the coming of heavy metal. It's a song so similar to the psychedelic rock styling of Syd Barrett-era Pink Floyd, it's very easy to image this song as a track from Piper at the Gates of Dawn, or a promise of what Barrett could have produced at some point in the future with Pink Floyd.

Like good comedy, the best was done early, and copied often. Along with Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath, Deep Purple helped create a new style of rock, and Machine Head is one of the finest examples. The album is a standout piece of guitar and keyboard wizardry that also maintains a humble but powerful drum/bass combination. The songs are timely in their development, and yet timeless in their influence on later artists. Just as Pink Floyd's psychedelic style was honed and fine-tuned into later masterpieces, Deep Purple's Machine Head became their signature work, their Dark Side of the Moon, defining the best of the band's ability.

Jacki Dimitroff is a staff writer for Spare Bricks. Special

thanks to staff writer Richard Mahon for his invaluable input to this column.

Discovering the inspiration for one of Pink Floyd's most enduring pieces

by Johan Lif

Editor's note: It has been Spare Bricks' policy to avoid reprinting material from other sources. With rare exception, we've stood by that. However, there are occasions where an article or posting to an Internet forum or mailing list is so illuminating or thought-provoking that it almost demands to be reprinted. This is one such piece. We're reprinting it here with minimal editing. It was originally posted in 1997 to Echoes. Those of you who have read it already will doubtlessly enjoy reading it again; those of you who haven't, prepare to be enlightened as you enter the heart of the sun....

• • •

When browsing the shelves of a store for used books in Uppsala, Sweden, I came upon a book called Poems of the late T'ang. I wasn't looking for it, it was a happy accident. It seems that this was the book Waters drew on for the lyrics of "Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun." Contrary to what Cliff Jones says, it's not a Waley translation. The translator is A.C. Graham, and the book was first published in 1965, which I suppose must have been the edition Waters used (there was a reprint 1968, but wouldn't that be a little too late?) My copy is the 1988 edition, a part of the Penguin Clasics series, ISBN 0-14-044157-3.

Here's my line-by-line account of the lyrics and their sources:

Little by little the night turns around

This line comes from an untitled poem by Li Shang-Yin (812-58), p. 147 in the book (iii)

Bite black passion. Spring now sets.

Watch little by little the night turn around.

Echoes in the house; want to go up, dare not.

A glow behind the screen; wish to go through, cannot.

It would hurt too much, the swallow on a hairpin;

Truly shame me, the phoenix on a mirror.

On the road back, sunrise over Heng-t'ang.

The blossoming of the morning star shines farewell on

the jewelled saddle.

[Heng-t'ang was a pleasure quarter; cf. Li Ho's High Dike.]

Counting the leaves which tremble at dawn

Taken from another Li Shang-Yin poem, "Willow" p. 154

Willow

['Willow eyebrows' is a phrase used for both willow leaves and arched eyebrows.]

Boundless the leaves roused by spring,

Countless the twigs which tremble in the dawn.

Whether the willow can love or not,

Never a time when it does not dance.

Blown fluff hides white butterflies,

Drooping bands disclose the yellow oriole.

The beauty which shakes a kingdom must reach through all the body:

Who comes only to view the willow's eyebrows?

Lotuses lean on each other in yearning

This line derives from "In Ch'i-an, on a Chance Theme"; by Tu Mu (803-52), p. 135

I Ch'i-an, on a Chance Theme

(First of two)

The setting sun is two rods high on the bridge over the brook,

Light floss of mist curls half way up from the shadows of the willows.

So many green lotus-stalks lean on each other in yearning!

....For an instant they turn their heads to the West wind behind them.

[The lotuses, like the poet, look toward the sunset and Ch'ang-an.]

Under the eaves the swallow is resting

No direct source for this line. Perhaps Waters created it with several lines in mind - on p. 75, we find "Back from a walk, I lie under the front eaves", and on p. 151: "Two swallows in the rafters hear the long sigh."

Poet: Han Yu

Evening: for Chang Chi and Chou K'uang

The sunlight thins, the view empties:

Back from a walk, I lie under the front eaves.

Fairweather clouds like torn fluff

And the new moon like a whetted sickle.

A zest for the fields and moors stirs in me,

The ambition for robes of office has long since turned to loathing.

While I live, shall I take your hand again

Sighing that our years will soon be done?

Poet: Li Shang-Yin

(vii)

Where is it, the sad lyre which follows the quick flute?

Down endless lanes where the cherries flower, on a bank

where the willows droop.

The lady of the East house grows old without a husband,

The white sun at high noon, the last spring month half over.

Princess Li-yang is fourteen,

In the cool of the day, after the Rain Feast, with him behind the fence, look.

....Come home, toss and turn till the fifth watch.

Two swallows in the rafters hear the long sigh.

Over the mountain, watching the watcher

This line, while emotionally in tune with several of the poems, doesn't seem to be in the book. Of course, mountains figure frequently in the poems, and watchmen appear from time to time too.

It is also interesting to note that the Chinese phrase for "going on a pilgrimage," ch'ao-shan chin-hsiang, actually means "paying one's respects to the mountain,". The mountain could be considered an empress or an ancestor before whom one must kneel. The recorded history of Taoism began during the second century A.D., and regarded mountains as home to immortals and as places where magic herbs to aid transcendence could be found. Confucians saw mountains as emblems of world order. In that context, this line could mean something like "I am observant of what is beyond this world". A less esoteric meaning could be that the sun is the "watcher", the great eye in the sky which rises over the mountain.

From "Questions to Heaven - The Chinese Journies of an American Buddhist" by Gretel Elrlich, Beacon Press

Breaking the darkness, waking the grapevine

I have no idea where this line comes from. It's not to be found in the book.

One inch of love is one inch of shadow

Taken from another untitled Li Shang-Yin poem, p. 146. Interestingly enough, Roger changed "ashes" to "shadow", which perhaps led him to create the line which follows it, "love is the shadow that ripens the wine".

The east wind sighs, the fine rains come:

Beyond the pool of water-lilies, the noise of faint thunder.

A gold toad gnaws the lock. Open it, burn the incense.

A tiger of jade pulls the rope. Draw from the well and escape.

Chia's daughter peeped through the screen when Han the clerk was young,

The goddess of River left her pillow for the great Prince of Wei.

Never let your heart open with the spring flowers:

One inch of loves is an inch of ashes.

Love is the shadow that ripens the wine

This is a line that, as far as I can tell, isn't in the book. There are many mentions of "wine", though.

"Wine" could tie in with "grapevine," as wine comes from grapes. But though the sun can make the grapevine grow, it is only with human care and skill can wine be created.

Witness the man who raves at the wall

Making

the shape of his questions to heaven

These lines derive from the last line of "Don't Go Out of the Door" by Li Ho (791-817): "Witness the man who raved at the wall as he wrote his questions to heaven", the man being a certain Ch'u Yuan. "Questions to Heaven" was one of his books.

Poet: Li Ho

Don't Go Out of the Door

The Heavenly Questions were written by Ch'u Yuan (c. 300 B.C.).

Why not call them 'Questions to Heaven'? Heaven is too august to be questioned, so he called them 'Heavenly Questions'. Ch'u Yuan in exile, his anxious heart wasted with cares, roamed among the mountains and marshes, crossed over the hills and plains, crying aloud to the Most High, and sighing as he looked up at heaven. He saw in Ch'u the shrines of the former kings and the ancestral halls of the nobles, painted with pictures of heaven and earth, mountains and rivers, gods and spirits, jewels and monsters, and the wonders andthe deeds of ancient sages. When he tired of wandering among them he rested beneath them; and he took the pictures which he saw above him as themes for writing on the walls his raving questions.

(From the preface to the Heavenly Questions in the Songs of Ch'u)

I plucked the autumn orchid to adorn my girdle.

(Ch'u Yuan, Encountering Sorrows)

Heaven is inscrutable,

Earth keeps its secrets.

The nine-headed monsters eat our souls,

Frosts and snows snap our bones.

Dogs are set on us, snarl and sniff around us,

And lick their paws, partial to the orchid-girdled,

Till the end of all afflictions, when God sends us his chariot,

And the sword starred with jewels and the yoke of yellow gold.

I straddle my horse but there is no way back,

On the lake which swamped Li-yang the waves are huge as mountains,

Deadly dragons stare at me, jostle the rings on the bridle,

Lions and chimaeras spit from slavering mouths.

Pao Chiao slept all his life in the parted ferns,

Yen Hui before thirty was flecked at the temples,

Not that Yen Hui had weak blood

Nor that Pao Chiao had offended Heaven:

Heaven dreaded the time when teeth would close and rend them.

For this and this cause only made it so.

Plain though it is, I fear that still you doubt me.

Witness the man who raved at the wall as he wrote his questions to Heaven.

Whether the sun will fall in the evening

Not in the book. Perhaps Waters created it with the "Questions to Heaven" in mind.

Will he remember the lesson of giving?

Not to be found in the book. Many Chinese poems end with a question; maybe Waters decided to write his own Chinese-flavoured conclusion.

So what are we to make of those lines that aren't in the book? There are several alternatives: 1) Roger used another source; 2) The lines escaped me and are in fact lurking somewhere in the book (not very likely - it's only 171 pages, and I've been through them a few times); 3) They are Roger's own poetic creations. This last option seems the most likely one to me, especially seeing that Waters didn't slavishly follow the source book and most lines are altered in some way.

Anyway, I think this discovery settles some lyrical disputes: it's "yearning" rather than "union", "one inch" rather than "knowledge", "witness" rather than "who is", "raves" rather than "waves" or "arrives", "to heaven" rather than "by asking". Is it "counting" or "countless"? I don't know.

I found something else too: the Li Ho poem "On the Frontier" includes the line "On the Great Wall, a thousand miles of moonlight". It seems that Roger borrowed the words "a thousand miles of moonlight" for "Cirrus Minor." And one poem by Lu T'ung is called "The Eclipse of the Moon". Sounds familiar, doesn't it?

• • •

Many thanks to Johan Lif for his permission to reprint this piece in Spare Bricks.