|

The

River Rolls: The

River Rolls:

Understanding A Momentary Lapse of Reason

by

Dave Ward

Pink

Floyd’s 1987 release, A Momentary Lapse of Reason,

is among the least examined, most misunderstood albums in the

entire Pink Floyd canon. Pink

Floyd’s 1987 release, A Momentary Lapse of Reason,

is among the least examined, most misunderstood albums in the

entire Pink Floyd canon.

Many Floyd fans still dismiss

the album out-of-hand, primarily because Roger Waters disapproves

of it. This quick dismissal is often validated by other criticisms:

That the lyrics are poorly written, that there is no concept behind

it, that it lacks the “tooth” of previous Floyd albums,

or that it was an insincere effort to imitate the past glories

Pink Floyd had already achieved.

A Momentary Lapse of Reason deserves to be judged, for

good or bad, by the actual content of the album. To test the traditional

criticisms of the album, let’s take a closer look at the

lyrics—and the artwork as well—from A Momentary Lapse

of Reason.

The album opens with sound effects. Of course, it’s neither

the first nor last time nonmusical sound effects opened a Pink

Floyd album. For examples, Meddle opens with howling winds,

Dark Side of the Moon opens with a heartbeat, The Final

Cut opens with radio sound effects, and The Division Bell opens with radio telescope sounds.

A Momentary Lapse opens with the sound of rowing on a

river: paddle splashing, the oars creaking. At 1:15 into the song,

we hear Nick Mason recite some words:

When the childlike view of the world went,

Nothing replaced it... I do not like being asked to... Other

people replaced it—

Someone who knows.

It’s impossible to apply an interpretation to so few words

without very uncertain, risky speculation. The words could possibly

be about Syd Barrett, the original shining star of Pink Floyd. Barrett

certainly had a childlike view of the world, expressed in his lyrics,

innocent and playful—yet sometimes dark, lonely and world-weary.

When Barrett’s childlike view left him as his latent schizophrenia

asserted itself, certainly nothing replaced it. The “nothingness” of Barrett’s mental illness is addressed in previous Pink Floyd

songs such as “Shine On You Crazy Diamond” in which this

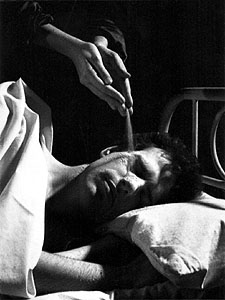

absence is compared to “black holes in the sky.” The film which accompanies “Signs of Life” in concert

offers possible further clues. A man rows a boat on a river. The

camera angle sometimes sinks below the surface of the water, showing

the green murkiness which lies beneath.

Rivers, and bodies of water in general, are a virtually universal

symbol of the unconscious aspects of the mind: artistic creativity,

latent emotions, and impulses within us that motivate us without

our notice or control.

Barrett himself used drowning in water as a symbol of his own

internal turmoil in “Astronomy Domine.” In those lyrics,

“the blue you once knew” references the blue skies which

he would no longer see—the blue sky itself being a metaphor

for happiness and contentment. Barrett describes an underwater

struggle, a struggle which is of himself against himself.

This same struggle was depicted by the post-Barrett Floyd in

a film which accompanied live performances of “Shine On You

Crazy Diamond.” That film, a blatant allegory for Barrett’s

story, depicted Barrett plunging into a deep pool and fighting

himself underwater.

It’s entirely possible that the film for “Signs of

Life”—made by Storm Thorgerson, who also made the “Shine

On” film—is intended to suggest Barrett again.

Yet, as compelling as it is to apply a Barrett reference to

these few words from “Signs of Life,” we have to acknowledge

that there is simply too little here to be at all certain of the

reference or meaning. It could just as well be about many other

things.

The second song on A Momentary Lapse of Reason is “Learning

to Fly.” The lyrics are the most refined on the album, more

focussed than “Yet Another Movie” and less redundant

than “Sorrow.” “‘Learning to Fly’ is about breaking free and

the actual mechanics of learning to fly an airplane,” Gilmour

said in the December 1987 issue of Only Music. It is widely

understood that on another level this flight is a metaphor for

spirituality and independence.

This is brought into focus by the story video for the song.

Drawing from a Native American tale, the video depicts a young

man who, with the encouragement of a Native American elder shaman,

leaps from a cliff and is transformed into an American Bald Eagle.

But flight and spiritual independence is not the only meaning.

The lyrics also deal with persistence and perseverance. The subject

of the song sees that “ice is forming on the tips of my wings.” Any aerophile knows that ice on the wings of an aircraft is potentially

deadly, and is something pilots must constantly fight. The ice

here is serving as a metaphor for anything which holds a person

back, particularly their own inner doubts and fears which can

cause hesitation or stalling.

Despite the ice, the pilot still flies “above the planet

on a wing and a prayer.” Seemingly the pilot overcomes the

ice and flies anyway, achieving “suspended animation, a state

of bliss.” Where “Learning to Fly” is a song of encouragement

and victory, “Dogs of War” moves directly into Roger

Waters’ own territory: scathing anti-corporate, antiwar lyrics

with hints of socialism.

“Dog of War” could, in some ways, be compared to “Dogs” from the Animals album. In both songs, corrupt back room

wheeler-dealers are portrayed as vicious dogs who kill in order

to gain more power.

In “Dogs” the corrupt individuals are specifically

business men. The lyrics suggest that they are out to gain power

and money regardless of the cost inflicted on others who are weaker

than they. Waters also covers the eventual twofold demise of the

dogs: first he suggests that they will get old and fat, and finally

die of cancer, then later in “Sheep” he says that the

powerless will rise up and overthrow the dogs.

But in “Dogs of War” Gilmour is commenting on war-for-money

and the mercenary practices which became particularly common in

the mid-1980s. The “dogs” Gilmour addresses are politicians

and mercenaries. Gilmour’s dogs are not going to die as Waters’ dogs. In this case, “whatever may change, you know the dogs

remain.” The politicians make “invisible transfers and long distance

calls,” arranging for mercenaries to remove their political

opponents. The “laughter in marble halls” is that of

dealing between the apparently chummy politicians and mercenaries.

It is widely believed that in 1984 President Ronald Reagan of

the United States, with Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North, hired

mercenaries and drug smugglers to ensure that contras in Nicaragua

could keep receiving arms from the US, despite Congress outlawing

CIA-supplied arms in that year. There have been other allegations

of dealings between US politicians and mercenaries in the mid-1980s,

such as suggestions that mercenaries were trained for a planned

commando raid inside the Soviet Union.

It seems certain that “Dogs of War” is a reference

to the Reagan-era covert war dealings with Nicaraguan contras

and others.

The

next song, “One Slip,” is one of the very few Pink Floyd

songs which addresses sexual relationships. If nothing else convinces

Roger Waters fans that A Momentary Lapse has merits, Gilmour

should at least get credit for handling the topic of relationships

in a challenging, uncomfortably honest manner which elevates “One

Slip” far above almost all other relationship songs in rock

‘n’ roll. The

next song, “One Slip,” is one of the very few Pink Floyd

songs which addresses sexual relationships. If nothing else convinces

Roger Waters fans that A Momentary Lapse has merits, Gilmour

should at least get credit for handling the topic of relationships

in a challenging, uncomfortably honest manner which elevates “One

Slip” far above almost all other relationship songs in rock

‘n’ roll.

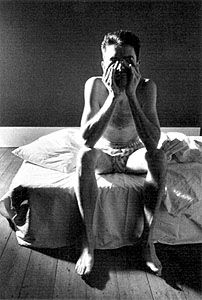

“One Slip” is not ultimately about sex or love, but

about unintended consequences. In the song, a man spots a woman

across the room. Their eyes meet, and soon they are both giving

in to sexual impulses. A pregnancy results, as is subtly implied

with the words “soon the seeds were sown” and “the

year grew late,” as well as by the sound effects at the beginning

of the song which are a metaphor for sperm trying and then contacting

the ovum.

The “momentary lapse of reason” is a reckless sexual

indulgence, without protection, which “binds a life to a

life” via the unplanned child. We know that “neither

one wanted to remain alone” as the pregnancy progressed, which

implies that if the pregnancy was unplanned, at least the man

involved was ready to take responsibility.

Although popular when the album was new, “On the Turning

Away” may be a bit more lyrically facile than anything else

on the album. The song is essentially a simple political commentary

urging compassion and a return to humanity and consideration for

others around us who are in need.

“‘Turning Away’ is about the political situations

in the world,” Gilmour said in the December 1987 issue of

Only Music. “We have these rather right-wing conservative

governments that don’t seem to care about many things other

than looking after themselves.” It’s a theme which has been addressed countless times,

from “We Are the World” to Rush’s “Closer to

the Heart.” Gilmour hasn’t done anything particularly

new here. Phrases like “using words you will find are strange/

mesmerized as they light the flame” seem unfocussed and disposable,

adding nothing in particular to the song except nice-sounding

combinations of words.

And yet, it has to be said in the song’s favor that “On

the Turning Away” still manages to come off as more mature

and sophisticated than either “We Are the World” or “Closer

to the Heart,” or indeed most other songs urging brotherly

compassion. (Although to be fair to Rush, Neil Peart was only

about 20 years old when he penned those lyrics, whereas Gilmour

was double that age upon writing “On the Turning Away.”)

“Yet Another Movie” is the most unfocused, vague lyric

on the album, but this is not necessarily a bad thing. The lyrics

depict little emotional incidents and images as if viewed on a

screen, perhaps from a detached perspective—a stark contrast

to the emotional connections urged by the previous song.

“It’s a more surrealistic effort than anything I’ve

attempted before,” Gilmour said in the December 1987 Only

Music. “Surreal” is an apt term for the song, where

images jump quickly from a running man, to a crying child, to

deceived women, to the sun, and and empty bed—all that in

just one of the six verses!

“I don’t even know what all of it means myself!” Gilmour has admitted.

I’m not convinced that there really is a meaning in “Yet

Another Movie,” nor that there should be a meaning.

The song appears to be simply a collection of succinct lyrical

snapshots, like glimpses of scenes while flipping quickly through

television channels. There doesn’t seem to be any one consistent

theme within the verses. It could be that the song is simply poetry

for the sake of poetry, with meaning being entirely irrelevant

to the purpose of this particular effort.

“Round

and Around,” the instrumental coda to “Yet Another Movie,” is impossible to analyze as it has no lyrics. It probably is simply

a nice instrumental with no message or meaning intended. The only

suggestions we have come from the title and a small woodblock

engraving which illustrates the song in the A Momentary Lapse

of Reason songbook. The tiny picture depicts an astronaut

with a Gemini-era spacesuit tethered for a space walk in orbit.

Taken with the title, space flight and orbit is implied. But there

is no ground for reading much into that. The track is best enjoyed

as the unusual 5/4 meter instrumental it is. “Round

and Around,” the instrumental coda to “Yet Another Movie,” is impossible to analyze as it has no lyrics. It probably is simply

a nice instrumental with no message or meaning intended. The only

suggestions we have come from the title and a small woodblock

engraving which illustrates the song in the A Momentary Lapse

of Reason songbook. The tiny picture depicts an astronaut

with a Gemini-era spacesuit tethered for a space walk in orbit.

Taken with the title, space flight and orbit is implied. But there

is no ground for reading much into that. The track is best enjoyed

as the unusual 5/4 meter instrumental it is.

“A New Machine, Parts 1 and 2” are often misinterpreted

by fans who are eager to read comments about Roger Waters or the

band itself into the lyrics. It has been previously suggested

that the lyrics may related to Nick Mason’s lack of confidence

when he first rejoined Gilmour. The lyrics have also been misinterpreted

as saying that the band Pink Floyd is a machine.

In fact, the simple lyrics to “A New Machine, Parts 1 and

2” delve into one of the richest areas of myth and metaphor:

the metaphor of The Wasteland.

In his poems “The Wasteland” and the more succinct

“The Hollow Men,” T.S. Eliot used deserts and detached

eyes as images representing an empty, unfulfilling life. The same

idea has been touched on in countless myths, legends, and poems:

loss of power over one’s own life, impotency to control one’s

own destiny, and losing touch with your passions and your bliss.

The theme runs in a sharp contrast against the joy and freedom

of self-direction covered in “Learning to Fly” earlier

in the album.

“A New Machine” depicts the subject as trapped within

the limitations of a body, seeming to look forward to death and

escape. This is not unlike the Buddhist and Hindu belief that

life is all sorrow, and the ultimate goal is to escape that cycle

of suffering. However, the Buddhists and Hindus believe in reincarnation,

and that escape is finally achieved by mastering moral and spiritual

goals. “A New Machine” depicts the longing for escape,

but not any particular method.

In “The Hollow Men,” Eliot uses references to the eyes

of “hollow men” to repeatedly express fear of death,

unwillingness to confront others’ suffering, and to bring

attention to the cold detachment in which he felt people are living,

with little compassion or connection to each other.

Gilmour similarly states, “I have always looked out from

behind these eyes,” suggesting that the subject is actually

within or behind the physical body, and the body is not who he

(or she) is. Where Eliot uses eyes to describe the detachment

between people, Gilmour uses eyes to emphasize one’s detachment

from one’s own self, a sort of spiritual vacancy.

Where Eliot describes a fear of death and unwillingness to confront

it, Gilmour’s subject looks forward to the day of death,

as if the real “self” will be freed when the body is

shed.

It’s

possible to speculate a comparison between “A New Machine” and the later Floyd song “What Do You Want From Me.” As in the latter song, “A New Machine” could potentially

be interpreted as a protest against the demands of his fans and

the music industry who would apparently like Gilmour to simply

keep churning out songs and touring, at the expense of his own

personal life and other things that may be important to his own

happiness. It’s

possible to speculate a comparison between “A New Machine” and the later Floyd song “What Do You Want From Me.” As in the latter song, “A New Machine” could potentially

be interpreted as a protest against the demands of his fans and

the music industry who would apparently like Gilmour to simply

keep churning out songs and touring, at the expense of his own

personal life and other things that may be important to his own

happiness.

“Terminal Frost” is the third and final instrumental

on A Momentary Lapse of Reason, and is also the longest

instrumental of the album. As with “Round and Around,” there is no significant content by which to discern any particular

meaning or message behind the song. The title alone is not enough.

Even the photograph accompanying the song in the song book fails

to suggest any meaning clearly. It is probably best enjoyed for

what it is: an excellent instrumental, atypical of anything Pink

Floyd had ever done before.

The final song of the album is “Sorrow.” Although it

is in some ways lyrically redundant, it is the pinnacle of the

underlying imagery which pervades the entire album.

“Sorrow” addresses a longing for past glories. The

setting of the song appears to be a post-apocalyptic world, but

this is unclear. It could as well be set in the present, with

its reference to air pollution and oil spills. “‘Sorrow’ is a bit of a lost paradise,” Gilmour said in Only Music,

December 1987.

At its heart, “Sorrow” is another step into T.S. Eliot’s

imagery. Eliot uses an arid wasteland as a metaphor for spiritual

death and joylessness. Gilmour’s wasteland has plenty of

water in the form of rivers and seas, but the air and water are

polluted. The subject of the song is clearly hopeless, being “chained

forever to a world that’s departed.” Near the end of “The Hollow Men,” Eliot describes a

“shadow” which comes between the intentions behind an

action and the actual result. In this and other works, Eliot often

addressed impotency in one’s own life, an inability to turn

ambition into achievement. Likewise, in “Sorrow” Gilmour

describes the subject’s similar paralysis, with curdling

blood, trembling knee, weakening hand, and faltering step.

And what of an underlying theme in the album? A Momentary

Lapse of Reason is not a concept story-album in that the songs

do not collectively form a plot to tell a single story. However,

the imagery of water—particularly rivers—appears in

almost every lyric.

The album opens with a boat being rowed during “Signs of

Life.” In “Learning to Fly” the runway is likened

to a river, and there is a minor reference to the subject’s

“watering eye.” The Storm Thorgerson photograph illustrating

“One Slip” depicts a man and woman underwater swimming

toward a submerged bed. “Yet Another Movie” refers to

an empty bed (which for the cover became a pun on “river

bed”) as well as “the babbling that I brook” and

another mention of tears. “Sorrow” is full of multiple

mentions of rivers, to the point of being a bit redundant. Even

in “Dogs of War” the dogs are seen running through the

water on a beach.

“Originally

we wondered whether we ought to be looking for a concept album

and if things should be linked together,” Mason said in the

December 1987 Only Music. The band made some effort to

find a common topic, but couldn’t construct anything satisfactory. “Originally

we wondered whether we ought to be looking for a concept album

and if things should be linked together,” Mason said in the

December 1987 Only Music. The band made some effort to

find a common topic, but couldn’t construct anything satisfactory.

Gilmour later told Rolling Stone magazine in its 19 November

1987 issue, “We thought, ‘Sod this, we don’t have

to make a concept album. If we work on making everything great,

then maybe it will show itself to have some sort of linear form

later.” “We decided the atmosphere was the most important thing,” Bob Ezrin told Rolling Stone. “The concept really

just had to be a feeling that was pervasive.” Gilmour’s studio where much of A Momentary Lapse was written and recorded is located aboard the houseboat The Astoria,

which is moored on the River Thames. As the wrote and recorded,

the water was ever-present just outside the boat’s small

windows. That river found its way into many songs throughout the

album.

“The river became the motif,” Ezrin told Rolling

Stone. “It came up in all the songs. The river imposed

itself.” Storm Thorgerson was well aware of the river’s influence

on the album. In turn, he strengthened that concept which unified

the songs into a whole. Thorgerson filled the visual elements

with additional water references: boats being rowed on a river,

dogs running through the surf, swimmers approaching an underwater

bed... and of course, hundreds of empty beds along a shoreline.

Fans have been too eager to misunderstand and dismiss A Momentary

Lapse, seeing little meaning, and trying to force artificial

references to Roger Waters where there are none. Pink Floyd would

address their former bandmate Waters in several songs on their

next studio album, The Division Bell, but there is not

a single reference to Roger Waters on A Momentary Lapse of

Reason.

In retrospect, it is only the absence of a more firm concept

which makes the album slightly odd in the Pink Floyd discography.

Every album since Dark Side of the Moon has had a firm

concept, A Momentary Lapse being the sole exception. (Some

would argue that The Division Bell also has no firm concept,

but in the case of that album, there is some grounds for debate.)

Despite the swift dismissal A Momentary Lapse has been

granted by fans of Roger Waters and fans of Waters’ influence

over the band, there is really little ground for dismissing the

album out-of-hand. There is nothing to suggest any of the songs

are anything less than heartfelt. The lyrics, though not perfect,

are rich with multiple layers of meaning and timeless literary

themes. The album is not without fault, but it is certainly not

the fraud or failure which many claim it to be. It’s a far

more quirky album than we might tend to remember, and that is

a good thing.

Looking back on A Momentary Lapse of Reason nearly 14

years after its initial release, it becomes clearer what the album

was: David Gilmour and Nick Mason hoisting the Pink Floyd banner

without Roger Waters for the first time, testing the winds and

trying to find their footing.

A Momentary Lapse was to the post-Waters Floyd precisely

what A Saucerful of Secrets was to the post-Waters Floyd:

a very strong first effort from a band who had just lost their

creative catalyst and was experimenting in order to find out how

to strike out on their own.

In hindsight, A Momentary Lapse appears to be not only

a success in terms of sales and concert attendance, but also a

great artistic victory. It certainly deserves a fresh look, and

a renewal of acceptance from all Pink Floyd fans.

Dave Ward is a

contributor to Spare Bricks

|